Here in Canada, we are in the final stretch to put the abomination of cetacean captivity to rest forever. We have one captive facility left, Marineland Canada at Niagara Falls, and there will be no new ones. When our parliament banned the practice just over a year ago, Marineland was allowed to ‘grandfather’ their belugas, bottlenose dolphins, and one lone orca, and to continue operating. Within the new legislative context, they were essentially granted a license to continue exploitation-for-profit of highly intelligent, thinking, feeling beings. No one else will ever again be granted this privilege in Canada.

But in most places in the world, it’s still the case that not enough of the public has yet voiced its concerns to an extent that lawmakers have taken notice. Pockets here and there (it looks like California may be next), but it’s not yet a massive wave of change or a worldwide movement. More like a grassroots effort that looks to break out once in a while in random places, but which will one day be an unstoppable force.

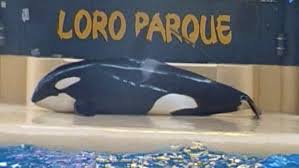

For now, the legal right to ‘own’ a cetacean and to use him or her as a profit-generating asset still holds in most places. This is certainly true in Tenerife, Spain (Canary Islands), where Morgan, pictured above, has been imprisoned for ten long years (see freemorgan.org, a founding member of Dolphinaria-Free Europe).

So in these environments, what is it that organizations like Loro Parque need to count on in order to continue operating – and to continue feeding dollars to the bottom line? Let’s take a moment to remember what some of these things are – be it for an aquarium, a hotel, a dolphin-therapy program, or a swim-with-the-dolphins program. What do they need to count on, and how do we take it away from them?

Here is some of what their survival depends on.

- That they control the narrative.

- That we rarely if ever respond as a unified block.

- That we don’t recognize that this fight is bigger than any one of our organizations, and fail to effectively take advantage of the synergies we are able to create when we collaborate.

- That we expend resources in competition with each other. Similarly, that we compete to divide the available dollars from the presently-existing donor pool, and don’t spend a lot of energy growing the size of that pool.

- That we spend all of our time repairing the damage caused by captivity, never being able to catch up, and end up losing a war of attrition.

- They are counting on us squandering some of our credibility by not carefully limiting the scope of what we’re calling for an end to. If they can push us out to the fringes where we are perceived by the public as radicals and eccentrics, we become much easier to defend against than a well-informed movement of concerned citizens.

- Finally, when the horrors of captivity peek through the carefully crafted façade and become obvious to us as patrons of the show, that enough of us will be willing to look the other way. The photo above is a case in point.

To date we’ve been doing a pretty good job of countering these, in most cases. Good enough that I believe we will eventually bring about the end of captivity one day. But we need to keep our eye on the ball. It matters how long this injustice persists, and the lives and liberty of 3,000 or so individuals are impacted in the meantime.

Each of these are topics we can and do expand upon elsewhere on cetacanada.org, but for now, let’s explore each of them just a bit more here…

For organizations like SeaWorld, Marineland and Loro Parque, it is vital to control the narrative. Keeping customers in the seats depends on selling the idea that their dolphins are happy and well taken care of. That the experience of viewing them will be positive and educational, as well as entertaining. They need you to believe that facilities such as theirs are essential to conservation efforts, and provide valuable research opportunities without which we could never come to properly understand these magnificent animals. In short, utter nonsense that masks what life in captivity is really like for a being of this nature.

Next, they need us to avoid speaking with one voice. At any given moment, there are a great many petitions, websites, social media campaigns, and so forth aimed at similar things, but I believe this masks the true size of the number of people who feel strongly enough to take a stand on any given issue. We have few coordinated campaigns. Normally a few thousand supporters here, a few thousand there, fighting much the same battle but rarely making apparent the true numbers behind an issue. Take ‘Honey’s’ case as an example. There had to be millions of us around the world, or at least many hundreds of thousands, who cared about the fate of this incredibly neglected dolphin. Yet, at no time did the appropriate authorities in Japan recognize the size and scope of a single unified voice on this issue sufficient to move them to act. She never did obtain her freedom, and died alone, after more than two years of complete isolation in an abandoned facility. We have to do a much better job of making the weight of our numbers felt.

Furthering the well-being of cetaceans around the world, and even just the single issue of ending their captivity in the entertainment industry, is a fight which is much bigger than any one of our organizations. We each need to focus on what we do best. And we need to collaborate effectively. This will maximize the total impact of our collective efforts.

Most of our organizations depend mainly on donations in order to function. We need to fundraise, which effectively brings us into competition for the donor funds available at any given time. This in itself is good, and necessary. We all need to make the case for why ours is an endeavor worthy of our donors’ support. What I would advise though, is that we do spend a significant portion of our energies on raising public awareness about the realities of captivity (and of course other issues), and continuously growing the size of our available donor pool.

As we’ve written elsewhere on this blog, the captivity industry gains a large measure of protection from the fact that they can take new captives far more quickly than we can repair the damage caused. It is difficult and expensive for us to fight the legal battles, to rehabilitate rescued dolphins in preparation for release back into the wild, or to build sanctuaries for those individuals who can’t be. We need to be raising awareness quickly enough to slow ticket sales and reduce the demand for new captives into the system. Otherwise, we end up chasing and never catching up, and risk losing a war of attrition.

This next one will be contentious with much of our activist community, but I think it needs to be said. (And we’ll need to discuss this further in future posts.) The sophisticated PR campaigns of companies like SeaWorld are counting on being able to brand those calling for an end to cetacean captivity as a fringe movement making unreasonable demands that the average person cannot get on board with. We can easily squander much of our credibility by not being careful in defining what we’re asking for. Expanding the scope too ambitiously risks endangering what is most important.

To use Canada’s Marineland as an example – caging a walrus, especially in the conditions that exist in their Niagara Falls facility, is deplorable and needs to end. But it’s not a crime in the same league as keeping a dolphin in a tank. A dolphin is a special case, and one which may well lead to personhood-rights one day. In order to protect this all-important premise, we want to give some thought to where we draw the line. #SaveSmooshi the walrus I can definitely get behind, but when we go much further and start calling for an end to the captivity of fish (as many of us do) we lose much of the public.

Finally – and it pains me to have to include this one – the captivity industry needs us to exercise a certain willful blindness to what goes on in their facilities. Though they go to enormous lengths to create an impression of dolphins happy and healthy in their marine park homes, the reality frequently pokes through the façade. When distress and despair become apparent to onlookers for a moment, the park needs you to forget what you’ve just seen. I’m talking about that dolphin banging his head against the plexi-glass, and when he turns towards you at just the right angle, it still looks like he’s smiling (because of the unfortunate physiological characteristic that his facial muscles are made that way). The park also needs the mother’s cries (as were heard from Morgan when the picture above was taken) to not penetrate your consciousness too deeply.

Don’t let yourself be a victim of such an utter lack of empathy. The industry is counting on it, but you have the power to deny them.

For The Orca’s Voice,

Dani, Canadian Cetacean Alliance

Leave a Reply