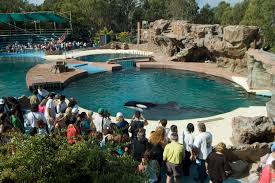

In the West, things have not been going well for enterprises offering entertainment that relies on captive whales and dolphins. As proof of this, check out SeaWorld’s stock price. This ‘Blackfish effect’ won’t be going away any time soon, or ever.

Here in Canada, public sentiment has risen to the level necessary to drive legislation that guarantees that Marineland Canada (and its current ‘inventory’ of belugas, bottlenose dolphins and a single orca) will be the last in this country.

Today, cetacean captivity is also banned in: Chile, Costa Rica, Croatia, France and India. It is strictly limited in the UK, Italy, New Zealand, Cyprus and several US states. Sanctuaries for formerly-captive cetaceans are coming into existence for the first time.

So the trending is going our way, in the sense that the general level of awareness in the public is clearly rising. That’s encouraging. But does it mean that time is on our side? No. I don’t believe it does, not unless you’re talking about the very long-term. At present, a significant proportion of our effort and resources goes into simply cleaning up the mess created by the captivity industry. That is, dealing with the consequences of the unjust and destructive practice of holding cetaceans captive. The more individuals get pulled into the system, the higher the percentage of our resources which need to be expended on simply trying to repair the damage.

Legal battles take time and money. Fighting for the individuals caught up in the most egregious violations of their rights – Honey (in Japan), Morgan(Spain / Canary Islands), Kiska (Canada) and Lolita (Florida, USA) is expensive. Imagine what it cost to free the belugas and orcas from the infamous ‘whale jail’ in Russia this past year, or to rehabilitate the dolphins rescued from Indonesia’s horrific travelling circuses. We must keep doing these things – we can’t take the pressure off for an instant – but it does put an enormous strain on our resources (almost all of which come from individual donations).

Evaluating whether a cetacean can be a candidate for a return to the wild, then the preparation for release, takes time and a lot of money. Building sanctuaries is expensive and difficult, and we are only now solving many of the technical challenges involved.

In short, we need to contain the damage as much as possible by moving the needle on public opinion as quickly as possible. That means raising awareness of the issues that impact cetacean well-being. Raising their profile. Increasing the number of people who recognize injustice when they see a cetacean in a concrete tank. That is the key to preventing the erosion of our resources just trying to keep up with expensive remedies. And it is our means to ending captivity for good.

The more of our resources we can pour into group 6, to push people out of that group and shrink the total pool, the better. (Oh, to have the funds to buy a 60-second ad during the Superbowl!!) For as long as that circle remains large, the captivity industry has a means of survival. They will never be able to sustain themselves from group 4. Not unless I’m completely wrong about the nature of my fellow human beings. And I’m not.

So we have the trending going our way, but I fear we risk losing a war of attrition. One large contributing factor is, ironically, the rise of affluence around the world. Aquaria and marine theme parks are sprouting up all over China, and to a lesser extent in countries like the UAE, and tourist hot spots all over the world.

The quickest path to victory is to be able to produce weapons much faster than your opponent can. In our case, the best way to do that is to target the vast pool of resources which, at present, is potentially available to both sides. It means showing the captivity industry for what it really is, and not what their public relations campaigns wish us to see. At this point in time, they can outspend us by a wide margin. But we have something they don’t. Our position is morally defensible in full light. Theirs is not.

The benefits of raising awareness among the general public are several.

Benefit #1 – We take the butts out of the seats at dolphin shows. Reduced demand means fewer dolphins that someone is going to supply. And rest assured, as long as there is demand, someone, somewhere in the world, out of our population of almost eight billion, will be willing to commit the terrible acts necessary in order to supply the dolphins.

The hunts in Taiji take place under the eyes of the world, and the hunters know that most watching are hoping for the hunt to fail. Every conceivable effort is made to hide the worst visuals from watching eyes. (Drones will also be banned over the area next season, on the ridiculous pretense that they pose a risk to the hunters’ safety.) Anything to buy time and prolong the existence of what is a very lucrative hunt. With the kind of money available, it will get done, by someone, regardless.

So as a general principle – we will NEVER cut off the supply, as long as demand exists (not that we shouldn’t continue to make the process as difficult as possible!). We have to attack this on the demand side. But to get potential patrons to #JustSayNo to the #DolphinShow, we need them to a) see the real horror behind the industry and b) gain an appreciation for the true nature of a cetacean. Thus making the horror of captivity that much the greater.

Benefit #2 – It makes it much easier to get legislation passed to ban captivity (such as Canada’s Bill S-203, passed in June, 2019). In fact, it’s the only way to get such things done in a democracy. Politicians are never going to shut down an entire industry unless they’re feeling the pressure of a significant voting block bearing down on them.

Benefit #3 – It puts much more pressure on enabling industries. Dolphins cannot get from where they were captured to the show pools hundreds, or usually thousands of kilometers away, without the complicity airlines. Tickets are increasingly booked online. That means big travel companies need to be involved. Cruise ships put stops at dolphin shows on the itinerary. IMATA’s trainers make the captive selections and receive the dolphins at the other end. Veterinary care has to be provided.

What happens when these people don’t want to work with the industry anymore, either from conscience or out of fear of bad PR (preferably the former, but I’ll take either)?

Benefit #4 – Investors will be more reluctant. Consider the lawsuits filed against SeaWorld, and $65M the courts ordered paid to investors defrauded by campaigns aimed at misleading them on the anticipated ‘Blackfish effects’.

Benefit #5 – If we continue to shrink the size of the potential pool of patrons, many of these people will become donors, volunteers, and spokespersons for our side.

So, we effectively have a race on our hands, with the stakes being the liberty and quality of life of thousands of individual non-human persons. There is zero question that awareness is growing. As well, a person who comes over to our side is very, very unlikely to ever go back. But let me issue the warning again. We run the risk of losing a war of attrition. Perhaps not in the long-run, but certainly over the next handful of decades. So there’s a great deal at stake.

Rehabilitation back to the wild, or building sanctuaries for those who can’t be, are enormously expensive undertakings. The industry can take new captives (presently several hundred per year) at a much faster rate than we can clean up the mess. Dolphins die much earlier in captivity than in the wild, thus spurring demand for replenishment.

We need to bring the base number down as quickly as we can. 3,000 needs to become incrementally smaller as quickly as possible so that we can eventually push it to zero. If the numbers go the other way, we can’t come up with enough Whale Sanctuary Projects, Sea Life Trusts, or Camp Lumba Lumba Dolphin Readaption Centers to win this. Not until every country on Earth has gone through a process of development and affluence, and then for the ethics of this to work their way through the culture.

The fact that we live in an information age at least means that this process will be much faster in say, China, than it was in my home country of Canada. None of us here thought much of it when Marineland Canada was ramping up in the 1960s and 70s. I can guarantee that wouldn’t be the case in Canada today. That’s helpful, but nevertheless…

The bottom line is, if 3,000 becomes 3,000 +1, and things head off in that direction, we will be at this for a long time. Which is why we need to aggressively attack the base right now. Raise awareness, to drain the potential pool of patrons, and take those dollars out of the industry. If we do that, everything else we need to do, from building sanctuaries, to ocean research, will be that much less difficult to do.

So putting every dollar we can into raising awareness among the public is where we’ll get our best return on investment.

For The Orca’s Voice,

Phil, and the CCA Team

Leave a Reply